DATA SET 1

November 2022

CONTEXTUALIZATION

Based on classroom context, prior assessment, and the students’ current learning goals, I determined that for my initial round of data collection, I would focus on students’ ability to move beyond summary-based writing, into written analysis based on critical thought and original inferences. I noticed during the first quarter of the school year that while my students were able to identify important information from a text and present that information as evidence in support of a claim, they were struggling to then convey how that evidence offered support to their claim, and why that support was significant in achieving their overall argument, or thesis. I then, through reviewing student work and talking with them one-on-one, isolated that the key skill students needed improvement in was expressing analysis and synthesis of key evidence, in writing specifically, as I noted that students in my class did not struggle as much to convey these kinds of critical thinking skills verbally. The learning and research construct, therefore, that I boiled the focus of my first data collection down to, is the expression of original inference and analysis in student-writing.

In my classes I teach and reinforce a specific paragraph model, which it is important to contextualize, as it is the basis of all scoring rubrics I use to review and collect data related to these constructs. This paragraph model is referred to as CeESS, which stands for the paragraph components of a claim, elaboration, evidence, support, and significance, respectively. CeESS is used in my class to teach and scaffold the writing process for body paragraphs within an extended analytical essay response. The model was introduced to me at River City High School in West Sacramento, CA, as a part of ERWC (Expository Reading and Writing Curriculum), which was developed by California State University, Sacramento. The CeESS model draws mostly on students' ability to meet 11th grade, California Common Standards for Writing, particularly W1 (Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence) and W4 (Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience). Table 1.1 below describes in more detail the expectations for students writing, per component of this model.

Table 1.1

Claim

Students must make a claim that directly references one or more aspects of their overall thesis statement (by extension this means it should also address one or more components of the writing prompt).

Elaboration

A student’s elaboration should directly follow the claim and is used to add additional detail to the statement made in the claim.

Evidence

Students must provide at least 1-2 pieces of evidence, from the text or source material, that relates to their claim. Evidence should be led into by context on the text or source material being referenced.

Support

In this portion of the paragraph students must make an inference, in order to answer the question, “How does the evidence support the claim?”. The key here is that students have gone beyond what's stated within the text and source material to better connect the pieces of their argument.

Significance

At the end of the paragraph students must assert to their reader, through additional analysis and synthesis, why all they’ve written so matters, and deepens understanding of the source material.

One of the reasons that I decided to introduce my English 11 students to the CeESS model is because, unlike other paragraph models, it uses clear terminology for each component of the paragraph, which by nature provides inherent directions for students to follow. For instance, Claim and Support are verbs or action words. Students can get confused by terminology such as “topic sentence” because it does not define what and how they should write, whereas “Claim” specifies the purpose their writing must serve. This benefit can be applied to each component of the CeESS model. Moreover, the CeESS components are relational, they work in tangent with one another. For example, Support must serve as a bridge between Claim and Evidence. Significance must draw on and extend the analysis provided by Support.

I determined that the CeESS components of Support and Significance best aligned with my inquiry construct of inference-making and critical analysis abilities. Since students are already familiar with the CeESS language and since those components serve as a key category of all their writing rubrics, which I use to score their work, I decided to focus on examining students’ performance in the Support and Significance categories for my first round of data collection.

COLLECTION

To actually conduct the data collection I focused on dissecting student writing, measuring their current abilities to provide Support and Significance in their body paragraphs, and therefore examined a few different variations of students’ rubric scores. Students were assigned a one paragraph formative writing assignment, where their primary task was to follow the CeESS model in order to analyze a rhetorical choice made within a speech that was watched and discussed in class. Students were provided with copies of the rubrics ahead of time, as well as sentence starters that were categorized by each component of CeESS, so they were well aware of the expectation to include each component in their argument and writing. Every student in this class, which is thirty-one in total, turned in a response and was included in the data collection.

After students turned in their work I went through an initial round of scoring, where I used a rubric with the following categories: Claim/Elaboration, Evidence, Support/Significance, Organization, and Language Mechanics. Each category was worth 10 points, for a total assignment value of 50 points. This was the rubric students were graded on. I paid close attention when scoring to Evidence and Support/Significance categories. I will discuss the results of this round of scoring further below.

I then went back through student responses and categorized them as either containing only Evidence, Evidence and Support, or Evidence, Support, and Significance. Sorting student work into these three categories helped me to really isolate how skilled they were or were not at conducting high level analysis and making inferences and connections based on the source material. I then separated out some student sample responses that exemplified the skill level of student writing which I felt marked each of these categories and which showed a distinct increase in range of analysis from the first student example (evidence-only) to the last (evidence + support + significance).

RESULTS

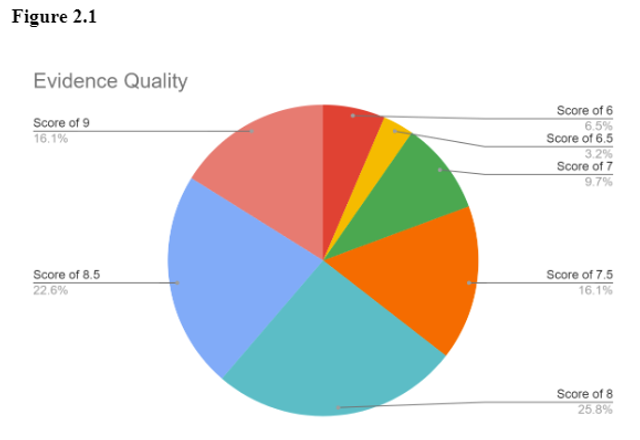

After the first round of scoring, using the five category rubric noted above, I found that in the Evidence category my 31 students had scored an average of 7.9/10. Table 2.0 shows the scores students received (by point value) in the Evidence category and Figure 2.1 shows the distribution of scoring across the Evidence category.

Table 2.0

Evidence Rubric Scores - Out of 10 Total Points

Amount of students that received that score -

Score of 5 - 0

Score of 6 - 2

Score of 6.5 - 1

Score of 7 - 3

Score of 7.5 - 5

Score of 8 - 8

Score of 8.5 - 7

Score of 9 - 5

In the Support/Significance category, which is most relevant to my inquiry construct, students scored only an average of 7.0/10. Table 3.0 shows the scores students received (by point value) in the Support/Significance catagory and Figure 3.1 shows the distribution of scoring across the Support/Significance category.

Table 3.0

Support/Significance Rubric Scores - Out of 10 Total Points

Amount of students that received that score -

Score of 5 - 3

Score of 6 - 5

Score of 6.5 - 5

Score of 7 - 6

Score of 7.5 - 5

Score of 8 - 1

Score of 8.5 - 1

Score of 9 - 5

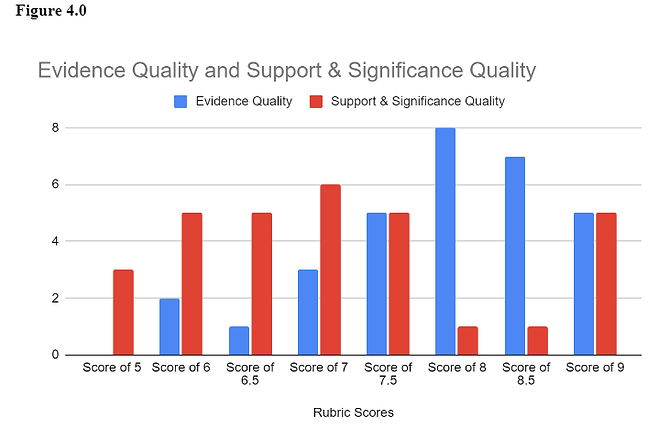

When examining this data, I felt that the distribution of these rubric scores was important to tracking student skill and progress, as it seemed to help contextualize and measure the quality of student evidence or analysis in their writing. As a key part of inference-making is moving beyond simply providing evidence, and toward making logical leaps, I decided that comparing the quality of writing between these two categories might be of note. Figure 4.0 demonstrates this comparison.

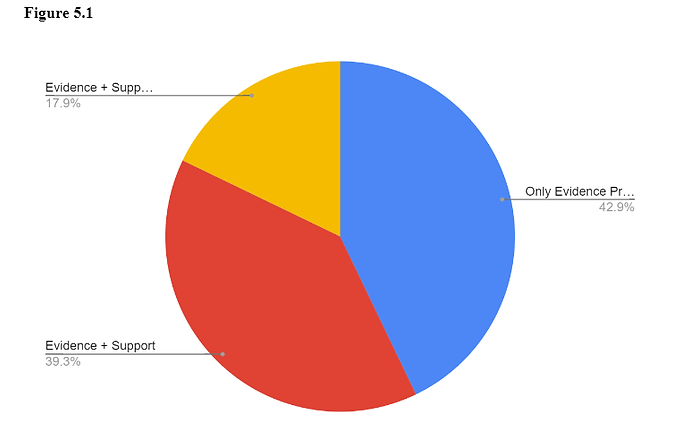

Finally, I examined the number of student responses that either included Evidence only, included Evidence and Support (the more surface level of the analytical components), or included Evidence and both analytical components, Support and Significance. Table 5.0 provides the number of student response which fall into each catagory. Figure 5.1 demonstrates the distribution of student responses across those three categories - which shows how many students are or are not currently capable of high-level inference making based on textual evidence in their writing.

ANALYSIS

This data ultimately reveals a lot about the way my students are currently writing, their comfort level with the CeESS format, and their inference-making abilities. To begin, by analyzing Table 2.0, Figure 2.1, and Table 5.0 we can note that all students included a piece of evidence from the source material in their response, that met the criteria for that category, and moreover only three students scored below a 7/10 in the Evidence category on the grading rubric. This tells me that my students are capable of pulling relevant information from the source material, that they believe will help support their claim. They can identify and integrate other’s ideas in order to support their own. I think there is still clearly room for improvement in terms of integrating the pieces of evidence, but in terms of selecting and including evidence in their writing, my students are proficient.

On the surface the average score in the Evidence category of 7.9/10 does not seem too far off from the Support/Significance category average score of 7.0/10. However, when I compared Figures 2.1, 3.1, and 4.0 I found that the distribution of scores between the two categories was vastly different. While the vast majority of students scored an 8/10 or above in the Evidence category, the same majority of students scored below a 7.5/10 in the Support/Significance category. There was a cluster of students, however, who scored quite highly in the Support/Significance category, and that skewed the average score, so that it represents a higher score than the majority of the class achieved on their analysis. In other words, if we compared the quality of evidence in students’ writing to the quality of students’ support/significance (analysis), we’d find that students' evidence quality was more consistent, especially across the 7.5-9 range of scores, whereas the quality of analysis was more polarized. What this tells me is that while, as established, the majority of students are proficient in including evidence in their writing, the same can not be said for support/significance. Inclusion of the support/significance components was inconsistent at best- with 43% of the class having not included satisfactory analysis in their writing, and an additional 39% of the class having only included partial analysis in the form of the more surface level support component (Figure 5.0). Even when students’ attempted to include these analysis components the scored were mostly below proficient, resting in 7.5-5 range of scores.

Although it is fair to note that the students who did include all analytical components, or both Support and Significance, were also the students with the highest scores in the Support/Significance category. This tells me that while the majority of the class is struggling with the Support and Significance components, those members of class who do get these analysis expectations really get it. That minority of students has progressed past proficiency and is working towards mastery of these components. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity in my future lessons. I will have to plan material that supports students who are still struggling with the basics of analytical writing, while also still challenging this group of students who have a slightly more advanced level of skill right now. One idea that might be of use, if these students are comfortable, is using their writing as examples, or conducting interviews or surveys with them to see what parts of my lessons helped them to grasp CeESS so quickly, so that I might amplify those helpful tactics to the rest of the class.

I am left wondering, after analyzing this data and considering my lessons leading up to this assignment, if students would have fared better if I had distinguished Support and Significance more. Because they were lumped together on the scoring rubric, and because I often refer to both of these components as “analysis” when teaching, students might not have picked up on the nuances between the two. Support is more surface level analysis, because it relies heavily on the evidence from the source material, and references the evidence directly, in order to connect the evidence and claim. Significance is a deeper level of analysis, where the student must build on the Support by moving away from any direct textual evidence and instead providing their own original inferences that prove or speak to the importance of their claim. In the future, I think I may try to better present these differences to students, since so many of them did not really attempt to include a Significance component in their writing. One way I might do this is by workshopping the Support and Significance components separately, starting with Support in one lesson and building to Significance in the subsequent lesson, so that students can better understand the expected progression of analysis in their writing. Another way is by modifying my rubric so that I score these two components separately.

Another place where I feel my lessons can be improved, in order to help students sharpen these skills and improve their inference-making in writing, is by allowing students time and space to respond to writing prompts verbally, or workshop their Support and Significance verbally. I postulate that if I engaged students in active literacy based activities, which would allow them to think abstractly, form new and creative connections, and then express those ideas verbally and tactically, before attempting to write, that their Support and Significance components would be deeper and more inferential.

My next steps will include modifying lessons to distinguish Support and Significance more, and then editing the CeESS paragraph rubric to reflect that those are separate analytical components in their writing. Students will be beginning a short unit on research paper writing, using sources that they found in history class. Building explorative analysis based on these sources will be crucial. I am considering building several writing workshops that use active literacy strategies as a way for students to spatially interpret the connections between different components of the CeESS model, and formulate components of their analysis verbally before writing. This would involve modified versions of Story Whoosh, Freeze Frame, Spectrum (having students move information along a physical spectrum), and Vocabulary Statues activities. At the end of the unit, students will complete a writing assignment, which I would then score on the modified rubric in a similar process to this round of data collection.